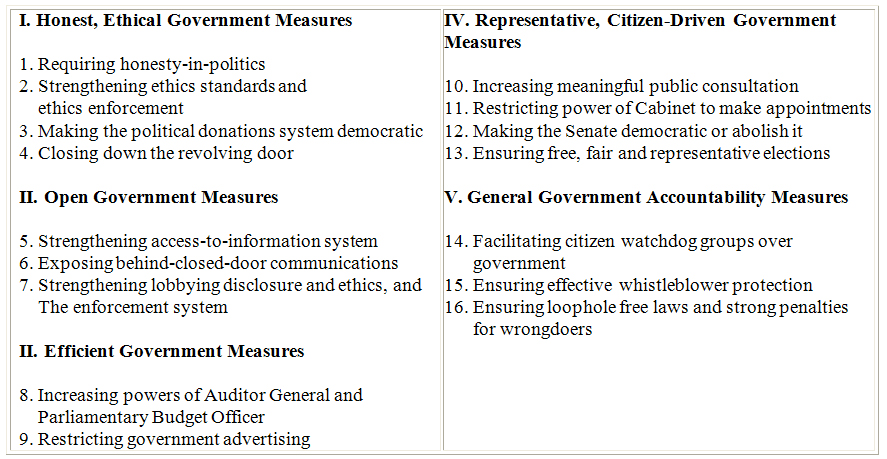

I. Honest, Ethical Government Measures

SECTION I OVERALL GRADES

Bloc Québécois – D

Conservative Party – D-

Green Party – B

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – D

1. Requiring honesty-in-politics – Pass a law that requires all federal Cabinet ministers, MPs, Senators, political staff, Cabinet appointees and government employees (including at Crown corporations, agencies, boards, commissions, courts and tribunals) nomination race, party leadership race and election candidates to tell the truth, with an easily accessible complaint process to a fully independent watchdog agency that is fully empowered to investigate and penalize anyone who lies (including during elections through online election posts or ads). (Go to Honesty in Politics Campaign, and Stop Fake Online Election Ads Campaign, for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – A-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – C

2. Strengthening ethics standards for politicians, political staff, Cabinet appointees and government employees, and ethics enforcement – Close the loopholes in the existing ethics rules (including requiring resignation and a by-election if an MP switches parties between elections) and apply them to all government institutions (including all Crown corporations), and as proposed by the federal Department of Finance place anyone with decision-making power on the anti-corruption watch list of the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (Fintrac) so deposits to their bank accounts can be tracked, and; strengthen the independence and effectiveness of politician and government employee ethics watchdog positions (the Ethics Commissioner for Cabinet and MPs, the Senate Ethics Officer for senators, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner for government employees, the Commissioner of Lobbyists for lobbyists) by giving opposition party leaders a veto over appointees, having Parliament (as opposed to Cabinet) approve their annual budgets (as is currently the process for the Ethics Commissioner), prohibiting the watchdogs from giving secret advice, requiring them to investigate and rule publicly on all complaints (including anonymous complaints), fully empowering and requiring them to penalize rule-breakers, changing all the codes they enforce into laws, and ensuring that all their decisions can be reviewed by the courts. (Go to Government Ethics Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – C

Conservative Party – C

Green Party – C

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

3. Making the political donations system democratic – Prohibit secret, unlimited donations of money, property or services by anyone for any reason to nomination and party leadership candidates (only such donations are now only prohibited if given to election candidates); limit loans, including from financial institutions, to parties and all types of candidates to the same level as donations are limited; require disclosure of all donations (including the identity of the donor’s employer (as in the U.S.) and/or major affiliations) and loans quarterly and before any election day; limit spending on campaigns for the leadership of political parties; maintain limits on third-party (non-political party) advertising during elections; lower the public funding of political parties from $2 per vote received to $1 per vote received for parties that elect more MPs than they deserve based on the percentage of voter support they receive (to ensure that in order to prosper these parties need to have active, ongoing support of a broad base of individuals) and; ensure riding associations receive a fair share of this per-vote funding (so that party headquarters don’t have undue control over riding associations). (Go to Money in Politics Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – B

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – A-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – B-

4. Closing down the revolving door – Prohibit lobbyists from working for government departments or serving in senior positions for political parties or candidates for public office (as in New Mexico and Maryland), and from having business connections with anyone who does, and close the loopholes so that the actual cooling-off period for former Cabinet ministers, ministerial staff and senior public officials is five years (and three years for MPs, senators, their staff, and government employees) during which they are prohibited from becoming a lobbyist or working with people, corporations or organizations with which they had direct dealings while in government. Make the Ethics Commissioner, Commissioner of Lobbying and Senate Ethics Officer more independent and effective by requiring approval of opposition party leaders of the person appointed to each position, by having Parliament (as opposed to Cabinet) approve the Commissioner of Lobbying’s annual budget (as is currently the process for the Ethics Commissioner), by prohibiting the Commissioners from giving secret advice, by requiring the Commissioners to investigate and rule publicly on all complaints (including anonymous complaints), by fully empowering and requiring the Commissioners to penalize rule-breakers, by ensuring all decisions of the Commissioners can be reviewed by the courts, and by changing the codes they enforce (MPs Code, Lobbyists’ Code and Senate Code of Conduct into laws. (Go to Government Ethics Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – B-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

II. Open Government Measures

SECTION II OVERALL GRADES

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – C-

Green Party – C-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

5. Strengthening access-to-information system – Strengthen the federal access-to-information law and government information management system by applying the law to all government/publicly funded institutions, requiring all institutions and officials to create records of all decisions and actions and disclose them proactively and regularly, creating a public interest override of all access exemptions, giving opposition party leaders a veto over the appointment of the Information Commissioner, having Parliament (as opposed to Cabinet) approve the Information Commissioner’s annual budgets (as is currently the process for the federal Ethics Commissioner), and giving the federal Information Commissioner the power and mandate to order the release of documents (as in Ontario, Alberta and B.C.), to order changes to government institutions’ information systems, and to penalize violators of access laws, regulations, policies and rules. (Go to Open Government Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – C+

Green Party – C+

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

6. Exposing behind-closed-door communications – Require in a new law that Ministers and senior public officials to disclose their contacts with all lobbyists, whether paid or volunteer lobbyists. (Go to Government Ethics Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – I

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

7. Strengthening lobbying disclosure and ethics, and the enforcement system – Strengthen the Lobbying Act and Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct disclosure system by closing the loophole that currently allows corporations to hide the number of people involved in lobbying activities, and by requiring lobbyists to disclose their past work with any Canadian or foreign government, political party or candidate, to disclose all their government relations activities (whether paid or volunteer) involving gathering inside information or trying to influence policy-makers (as in the U.S.) and to disclose the amount they spend on lobbying campaigns (as in 33 U.S. states), and; strengthen the ethics and enforcement system by adding specific rules and closing loopholes in the Lobbyists’ Code and making it part of the Act, by extending the limitation period for prosecutions of violations of the Act to 10 years, and; by giving opposition party leaders a veto over the appointment of the Commissioner of Lobbying, by having Parliament (as opposed to Cabinet) approve the Commissioner’s annual budget (as is currently the process for the Ethics Commissioner), by prohibiting the Commissioner from giving secret advice, by ensuring that the Commissioner must investigate and rule publicly on all complaints (including anonymous complaints), by fully empowering the Commissioner to penalize rule-breakers, and by ensuring all Commissioner decisions can be reviewed by the courts. (Go to Government Ethics Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – B-

Green Party – B-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

III. Efficient Government Measures

SECTION III OVERALL GRADES

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – D

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

8. Increasing powers of Auditor General and Parliamentary Budget Officer – Increase the independence of the Auditor General and Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) by requiring approval of appointment from opposition party leaders, and by making the PBO a full Officer of Parliament with a fixed term who can only be dismissed for cause; increase auditing resources of the Auditor General and PBO by having Parliament (as opposed to Cabinet) approve the Auditor General’s annual budget (as is currently the process for the federal Ethics Commissioner), and; empower the Auditor General to audit all government institutions, to make orders for changes to government institutions’ spending systems, and empower the Auditor General and PBO to penalize violators of federal Treasury Board spending rules or Auditor General or PBO orders o requests for information. (Go to Stop Fraud Politician Spending Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – C-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

9. Restricting government advertising – Empower a government watchdog agency to preview and prohibit government advertising that promotes the ruling party, especially leading up to an election (similar to the restrictions in Manitoba and Saskatchewan). (Go to Stop Fraud Politician Spending Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – I

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

IV. Representative, Citizen-Driven Government Measures

SECTION IV OVERALL GRADES

Bloc Québécois – D-

Conservative Party – D-

Green Party – C-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – C-

10. Increasing meaningful public consultation – Pass a law requiring all government departments and institutions to use consultation processes that provide meaningful opportunities for citizen participation, especially concerning decisions that affect the lives of all Canadians. (Go to Stop PM/Premier Power Abuses Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – C-

Green Party – C-

Liberal Party – D-

New Democrat Party – C-

11. Restricting power of Cabinet to make appointments – Require approval by opposition party leaders for the approximately 3,000 judicial, agency, board, commission and tribunal appointments currently made by the Prime Minister (including the board and President of the CBC), especially for appointees to senior and law enforcement positions, after a merit-based nomination and screening process conducted by finally setting up the Public Appointments Commission that was given a legal basis to exist under the so-called “Federal Accountability Act”. (Go to Stop Bad Government Appointments Campaign, and Stop PM/Premier Power Abuses Campaign, for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – B

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – I

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

12. Making the House more democratic, and making the Senate democratic or abolish it – Change the Parliament of Canada Act to restrict the Prime Minister’s power to shut down (prorogue) Parliament to only for a very short time, and only for an election (dissolution) or if the national situation has changed significantly or if the Prime Minister can show that the government has completed all their pledged actions from the last Speech from the Throne (or attempted to do so, as the opposition parties may stop or delay completion of some actions). Give all party caucuses the power to choose which MPs and senators in their party sits on House and Senate committees, and allow any MP or senator to introduce a private member bill at any time, and define what a “vote of confidence” is in the Parliament of Canada Act in a restrictive way so most votes in the House of Commons are free votes. Attempt to reach an agreement with provincial governments (as required by the Constitution) to either abolish the Senate or reform the Senate (with a safeguard that Senate powers will not be increased unless senators are elected and their overall accountability increased). (Go to Stop Muzzling MPs Campaign, and Stop PM/Premier Power Abuses Campaign, and Shut Down the Senate Campaign, and Democratic Head Campaign, for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – I

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – B-

13. Ensuring free, fair and representative elections – Change the current voting law and system (the Canada Elections Act) to specifically restrict the Prime Ministers’ power to call an unfair snap election, so that election dates are fixed as much as possible under the Canadian parliamentary system. Change the Act also so that nomination and party leadership races are regulated by Elections Canada (including limiting spending on campaigns for party leadership), so that Elections Canada determines which parties can participate in election debates based upon merit criteria, so that party leaders cannot appoint candidates except when a riding does not have a riding association, so that voters are allowed to refuse their ballot (ie. vote for “none of the above”, as in Ontario), and to provide a more equal number of voters in every riding, and a more accurate representation in Parliament of the actual voter support for each political party (with a safeguard to ensure that a party with low-level, narrow-base support does not have a disproportionately high level of power in Parliament). (Go to Democratic Voting System Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – B-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – B-

V. General Government Accountability Measures

SECTION V OVERALL GRADES

Bloc Québécois – D

Conservative Party – C

Green Party – D

Liberal Party – D-

New Democrat Party – D

14. Facilitating citizen watchdog groups over government – Require federal government institutions to enclose one-page pamphlets periodically in their mailings to citizens inviting citizens to join citizen-funded and directed groups to represent citizen interests in policy-making and enforcement processes of key government departments (for example, on ethics, spending, and health care/welfare) as has been proposed in the U.S. and recommended for Canadian banks and other financial institutions in 1998 by a federal task force, a House of Commons Committee, and a Senate Committee. (Go to Citizen Association Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – I

Conservative Party – I

Green Party – I

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

15. Ensuring effective whistleblower protection – Require everyone to report any violation of any law, regulation, policy, code, guideline or rule, and require all watchdog agencies over government (for example: Auditor General, Information Commissioner, Privacy Commissioner, Public Service Commission, the four ethics watchdogs (especially the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner), Security and Intelligence Review Committee, the National Health Council) to investigate and rule publicly on allegations of violations, to penalize violators, to protect anyone (not just employees) who reports a violation (so-called “whistleblowers”) from retaliation, to reward whistleblowers whose allegations are proven to be true, and to ensure a right to appeal to the courts. (Go to Protect Whistleblowers Who Protect You Campaign for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – B-

Conservative Party – B-

Green Party – B-

Liberal Party – I

New Democrat Party – I

16. Ensuring loophole free laws and strong penalties for wrongdoers – Close any technical and other loopholes that have been identified in laws, regulations, policies, codes, guidelines and rules (especially those regulating government institutions and large corporations) to help ensure strong enforcement, and increase financial penalties for violations to a level that significantly effects the annual revenues/budget of the institution or corporation. (Go to Stop Unfair Law Enforcement Campaign, and Corporate Responsibility Campaign, for details about Democracy Watch’s proposals)

Bloc Québécois – C-

Conservative Party – C

Green Party – D

Liberal Party – C

New Democrat Party – B-

|